Russia and China, controversial friends of the Czech president

Source: The Irish Times / www.irishtimes.com / By /

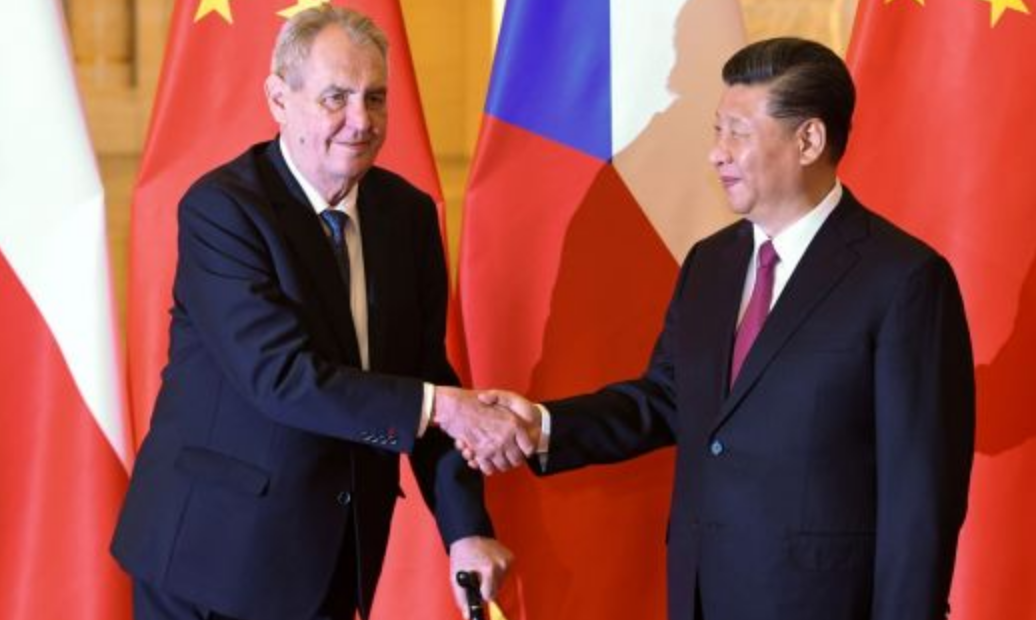

Milos Zeman’s ties with Putin and Jinping run counter to principles of the 1989 Velvet Revolution

Hundreds of thousands of Czechs are expected to gather in the streets of Prague this weekend, just as they did 30 years ago for rallies that swept away the communist regime and placed dissidents in charge of a bold new democracy.

Milos Zeman claims he was in the crowd when police attacked protesters on November 17th, 1989, sparking outrage that fuelled the “Velvet Revolution”, but he will not attend the commemorations, despite now being president of the nation.

Zeman (75) is the irascible champion of the many Czechs who feel let down by democracy and capitalism, cheated by the European Union, threatened by migrants, and nostalgic for certainties that crumbled along with the Soviet empire.

A proud drinker and smoker who mocks political correctness and liberal outrage (as when he waved an imitation Kalashnikov at reporters), Zeman could largely be ignored by Prague’s EU and Nato partners if it were not for his eagerness to make the Czech Republic a gateway to Europe for two difficult guests: Russia and China.

When playwright and former political prisoner Václav Havel became Czechoslovak president in December 1989, he served as a symbol of his nation’s escape from decades of Kremlin domination. Havel infuriated Beijing by supporting Taiwan, Chinese dissidents and exiled Tibetan spiritual leader the Dalai Lama.

Zeman quickly made clear that he did not share Havel’s qualms about dealing with autocrats

Havel left office in 2003, and when Zeman assumed the presidency a decade later, he brought a very different view of China and Russia to Prague Castle.

While aiming a steady drip of caustic comments at the EU, Zeman has urged the bloc to drop sanctions on Russia and joked with its president Vladimir Putin about “liquidating” journalists, and hailed China’s bid to expand global influence through infrastructure-building as “the most significant project in our modern history”.

Zeman quickly made clear that he did not share Havel’s qualms about dealing with autocrats, saying during a 2014 visit to Beijing that he had come to “learn how to increase economic growth and how to stabilise society” rather than “teach market economy or human rights”.

Military parade

The following year he was the only western leader to attend a huge military parade in China to commemorate the end of the second World War, when, alongside Putin, he watched soldiers march across Tiananmen Square, site of a 1989 massacre of pro-democracy protesters.

The Czech president’s official powers are mostly ceremonial, but Zeman brushed off concerns about his “parallel” foreign policy by claiming to have helped secure more than €1 billion in future Chinese investment for his country.

He also named a Chinese tycoon, Ye Jianming, as a personal adviser, having earlier raised eyebrows with the appointment of two top aides, Martin Nejedly and Vratislav Mynár, despite questions over their alleged links to Russia.

CEFC China Energy, then a rapidly growing company chaired by Ye, set up its European base in Prague and snapped up stakes in assets ranging from a brewery to hotels, an airline, a media business and a historic but struggling football club, Slavia Prague.

With money flowing in and another adviser to Zeman – former Czech defence minister Jaroslav Tvrdík – installed as chairman, Slavia’s fortunes began to pick up, and in the 2016-17 season they won their first national title in eight years.

Ye and CEFC did not enjoy the club’s success for long, however. In November 2017, a senior Chinese executive at a CEFC-sponsored think tank was charged in the US with bribing African officials, and three months later Ye was detained in Beijing for undisclosed reasons. He has not been seen in public since, having apparently fallen foul of figures more powerful than his own reputed close contacts in Chinese military intelligence.

In 2018 it was revealed that CEFC owed some €450 million to a Czech financial group, and its assets were swallowed up by a unit of Citic, a Chinese state-owned conglomerate; Slavia was then sold on to Chinese construction firm Sinobo.

“These Chinese projects weren’t really even investments in terms of creating new jobs. They were basically acquisitions and speculation,” says Jirí Pehe, the director of the New York University in Prague.

“China is looking for a place that could be used as a hub for its business expansion in Europe. And not only business, but other things ranging from intelligence activities to political activities,” says Pehe, who was an adviser to Havel.

“That’s obviously much easier to do in a country that doesn’t have much confidence and wants Chinese investments, and has politicians who are willing to totally reverse the stances that we had when Václav Havel was president,” he added.

“It was a huge embarrassment for Prague Castle, because Zeman chose Ye as an adviser and gave him an office at the castle, despite CEFC being suspected of being an operation of Chinese military intelligence,” Pehe says. “Any other politician would say, ‘Okay, I made a mistake.’ But this is not Zeman’s way.”

Lambasted

On several occasions, Zeman has publicly lambasted the Czech security services for raising the alarm over threats posed by China and Russia. The national cyber-security watchdog warned late last year that telecoms equipment made by Chinese supplier Huawei posed a security risk, prompting it to be banned from bidding for a €20 million contract to build an online portal for the Czech tax agency.

Huawei – which the US and several of its allies have also flagged as a security threat – denies posing any risk or co-operating with Chinese intelligence, and Mr Zeman has rallied to the company’s cause.

We have seen that Russia is increasingly using asymmetric tools and hybrid threats to spread their world view

“The current allegations against Huawei are groundless, and I hope to see Huawei’s continued development in the Czech Republic,” the firm quoted Zeman as saying during a visit to China in April.

Tomás Petrícek, the Czech foreign minister, insists that Zeman’s advocacy for Russia and China has not damaged international trust in the Prague government. “We’re not unique in having different representatives of the country with different opinions,” he says. “We can see all around Europe that democratically elected politicians might express very conflicting ideas. But at the end of the day, the Czech government is responsible for foreign policy and decisions of a substantive nature.

“This decision has been endorsed by the government,” Petrícek adds of the cyber-security agency’s risk assessment on Huawei, which critics accuse of providing a “backdoor” into electronic devices for Beijing’s intelligence services.

“It is the sovereign right of every country to ensure the safety of the infrastructure it needs for government and society to work well.”

When former double agent Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia were poisoned in Salisbury in England last year, Zeman argued that Moscow should not be blamed because a Czech lab had also produced the Novichok nerve agent that was involved. The British government dismissed his claim and expelled three Russian diplomats as part of a co-ordinated international response.

Zeman rejects Czech counter-intelligence service (BIS) reports on Russian threats as “blather”, but the agency continues to uncover alleged operations. BIS director Michal Koudelka told parliament last month that in 2018 his officers smashed a Russian cyber-spying network that had planned to attack the Czech Republic and its allies.

“It was created by people with links to Russian intelligence services and financed from Russia and the Russian embassy [in Prague],” he told deputies. “The network was completely dismantled and destroyed.”

We expect Russia to behave more responsibly in its neighbourhood and towards European states

Petrícek says his country is sensitive to possible Russian interference” in its affairs. “We have seen that Russia is increasingly using asymmetric tools and hybrid threats to spread their world view and influence internal democratic processes,” he explains.

“I hope one day there can be more trust between EU members and Russia . . . but at the same time we expect Russia to behave more responsibly in its neighbourhood and towards European states. It is clear that this is not happening at the moment.”

Analysts say China and Russia are also trying to expand their influence in the Czech Republic through educational, cultural and tourism programmes.

Obstacles

Beijing has hit more obstacles in recent months, however. This week, Prague’s prestigious Charles University shut down its Czech-Chinese Centre amid allegations that staff concealed money received from the Chinese embassy for conferences and other events.

The scandal has deepened scepticism towards China in Prague, where mayor Zdenek Hrib angered China this year by refusing to eject Taiwan’s ambassador from a diplomatic gathering and by flying the Tibetan flag from city hall.

Beijing accused Hrib of flouting the “one China” policy that the Czech government accepts, and in retaliation it cancelled tours by at least two Prague orchestras and scrapped a partnership agreement between the capitals.

“First, it revealed the true colours of Beijing, ie that they do not care about an apolitical partnership based on cultural exchange, but rather wish to pursue their political interests,” says Hrib.

“Second, China showed that it is not a trustworthy business partner, so we need not regret that we have lost the ‘sister-city’ agreement, from which only the Chinese side benefitted,” he tells The Irish Times.

Hrib is a member of the Pirate Party, which grew out of civil society and found widespread support for its anti-corruption message among critics of Zeman and Czech prime minister Andrej Babis, a billionaire tycoon who is dogged by allegations of corruption and of collaborating with the communist-era secret police.

In the Pirates’ strong defence of civic liberties and support for civil society – as well as Hrib’s solidarity with Tibet and Taiwan – Czechs hear echoes of Havel.

“Along with democracy and freedom, I really care about transparency. I also trust that public officials should have some scruples and avoid steps that violate the law or harm the interests of the country,” Hrib says.

“For this reason, I believe some kinds of conduct are inappropriate. For example, when the Prague Castle accepts Huawei as its ‘sponsor’, or when the prime minister, who is one of the richest Czechs, abuses his position to promote his company’s interests.”