Victims, not victors? The uniquely Czech debate over how to memorialise the Velvet Revolution

Source: The Guardian / www.theguardian.com / By Paul Wilson /

Prague has long an uneasy relationship with monuments to its history – but 30 years since the fall of the communist regime, that could be about to change

I used to think the saddest place in Prague was a prospect high above the Vltava River. It is a peaceful though somewhat neglected spot, buttressed by granite ramparts covered with graffiti and popular with families out for a stroll, skateboarders, joggers and tourists taking selfies against the backdrop of the city. At its centre is a gently mounded plateau, empty except for a giant metronome, soon to be taken down.

The area has no name on current maps of Prague, but it was once known, in popular parlance, as “U Stalina” – Stalin’s place. In 1955, two years after the Soviet dictator’s death, a massive 50-foot high granite monument to him was unveiled on this spot, the largest representation of Stalin in the world. Commissioned in the late 1940s when Czechoslovakia was being turned into a Soviet satellite state, and already under construction as Stalin lay dying, the monstrous memorial remained in place until 1962 when, in the spirit of de-Stalinisation, it was blown to smithereens by the same regime that erected it.

Over the past month, 30 years after a series of popular revolts cascaded through central and eastern Europe and swept Soviet-style totalitarianism into history, the city has seen hundreds of conferences, rallies, re-enactments, concerts and street parties commemorating what the Czechs call their Velvet Revolution.

Yet beneath the mood of celebration, you could feel a note of anxiety that can be summed up in a single question: with the rise of autocratic governments in Poland and Hungary, with the apparent fragility of the European Union, and with the bizarre alliances US president Donald Trump is forging with some of the world’s worst dictators, can the free-market democracy the Czechs have built over the past three decades survive? Given the history of the past century, during which Prague experienced eight abrupt and radically different regime changes and two military invasions, the question is not an idle one.

In its 4 November issue, the country’s most influential weekly magazine, Respekt, ran a small survey that in its own way encapsulated the uncertainty. The magazine asked a panel that included a sculptor, an historian of architecture, a former dissident writer and a young social activist: should Prague have a memorial to the Velvet Revolution? And if so, where should it be located?

Eda Kriseová, a writer who took an active part in the Velvet Revolution, told the magazine she couldn’t imagine a conventional memorial that would adequately represent an event that was “so alive, so spontaneous, so joyful”. In any case, she cautioned, “we haven’t had the best experience with stone memorials.”

Her answer points to a problem that is universal but particularly acute in Prague. Monuments erected in moments of political or historical zeal can quickly become embarrassing or even offensive when feelings and attitudes change. The movement to tear down or alter statues of racist colonial figures has become a global phenomenon.

The architecture historian Zdeněk Lukeš, who worked for over a decade in the Prague Castle under the late president Václav Havel, told Respekt he’d prefer to wait until the country emerged from its current political malaise before considering any grand, permanent memorial to 1989. The plaque that already exists on the site of the student demonstration that triggered the revolution is memento enough, he said.

When I asked Lukeš why he thought the Czechs were so quick to remove monuments to the past, he said it may have to do with a lack of certainty about their identity. By way of illustration, Lukeš told me a story about the fate of the statues depicting the country’s much-loved patriarch Thomas Garrigue Masaryk, who became president when Czechoslovakia was created in 1918.

Erected in several towns shortly after his death in 1935, the statues were taken down and buried when the Nazis occupied the country in 1939. After the second world war they were dug up and reinstated, only to be buried once more in 1948 when the communists seized power. During the Prague Spring in 1968, Masaryk was disinterred again, but then removed and buried after the Soviet invasion and occupation.

His final resurrection occurred after 1989, when he became a symbol of democracy restored. It all happened in the dark, as it were, with no public input or debate – and if the story seems amusing today, it’s also a sobering reminder of why the Czechs, even now, might feel their democracy, and their existence as a nation, to be more fragile than it is.

As if to ward off that capricious future, the most beloved Czech leader since Masaryk has no statue to him at all. Just as he once dominated the Velvet Revolution, Václav Havel, the playwright who became president, has loomed large over the 30th anniversary proceedings; according to a recent poll, 74% of young people between 18 and 29 consider him the best post-communist president.

Havel died in 2011, yet there are few memorials to him around the city, unless you count the modest plaque outside his post-presidential office in the centre of Prague, or “Havel’s Place” – a table and two chairs arranged as if for intimate conversation outside a restaurant on Maltézské Square in Prague’s Malá Strana quarter. The two places in Prague that bear Havel’s name – the city’s international airport, and a modest square behind the New Stage of the National Theatre – come with a touch of irony: Havel hated flying, and he hated the new National Theatre building.

The Velvet Revolution triggered a whole new wave of iconoclasm. In addition to the many plaques and busts of Lenin and of the first communist president, Klement Gottwald, hundreds of pieces of public art created during the communist era, most of them with no political or artistic significance, were removed without fanfare or regret. It also unleashed an unprecedented wave of bold creativity in public art.

The first and most spectacular example was an apparent act of creative vandalism when a Soviet tank, mounted on a pedestal as a monument to the Soviet liberation of Prague in 1945, was painted pink by a young sculptor, David Černý, in 1991. The action radically altered the meaning of the memorial while leaving it intact.

In the past 30 years Černý has become the most prolific Czech sculptor (at least since Matthias Braun, whose 18th-century sculptures are still standing on Prague’s Charles Bridge). Černý’s work ranges from the monumental, like the giant stainless-steel kinetic sculpture of Kafka’s head in the centre of Prague, to the subtle, like the enigmatic and barely noticeable “Embryo” installed as part of the downspout outside the Theatre on the Balustrade, where Havel premiered his early plays in the 1960s.

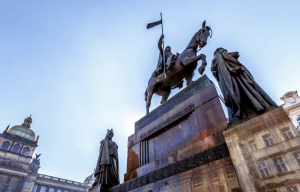

Černý’s Quo Vadis (Trabant), installed in the garden of the German embassy, is a reminder of the mass exodus of East Germans to the west before the Wall was breached on 9 November 1989; and his rendition of St Wenceslas – mounted on a dead horse suspended upside-down from the ceiling of the Lucerna Palace – was inspired by a period of political depression in the late 1990s. His works radiate a self-deprecating humour that seems intrinsic to the Czech nature, though it seldom finds expression in its public art.

One sign that Prague is becoming a normal country again is the current controversy over a statue erected in 1980 to honour the Soviet field marshal Ivan Stepanovich Konev. He led the army that drove the Germans out of part of Czechoslovakia at the end of the second world war, but he also crushed the Hungarian uprising in 1956 and is suspected of having helped plan the Soviet occupation of Czechoslovakia in 1968.

A vicious social media campaign, rumoured to be fuelled by Russian trolls, spread misinformation about him, and he and his family received death threats and were placed under police protection. The Prague 6 council has voted to relocate the statue to “a dignified place”, most probably to a newly proposed Museum of Memorials of the Twentieth Century. But the controversy is still simmering, and is yet another reminder of continuing tension between the Russians and the Czechs.

As if to acknowledge that victory can be ephemeral, the public memorials that do survive over time tend to honour the victims and martyrs of Czech history rather than its victors. A monument to Jan Hus, an early religious reformer who was burned at the stake for heresy in 1415, was erected in Prague’s Old Town Square in 1915, and has lasted through the many regime changes since then. The city walls still hold many small plaques and niches commemorating people killed during clashes with the retreating Germans at the end of the second world war, or who died confronting Warsaw Pact troops during the invasion of August 1968.

Olbram Zoubek’s memorial to the victims of communism – a set of skeletal figures arranged on an illuminated staircase to nowhere – is popular with visitors to Prague, as is the memorial to Jan Palach, the student who burned himself to death on Wenceslas Square in 1969 as a protest against the Soviet occupation. Until recently, there was even a plaque to Milan Hlavsa, the founding member of the much-harassed underground band I once played with, the Plastic People of the Universe. It had a slot where, for a crown, it would play his most famous song, The Destroying Angel.

The sculptor Pavel Karous, who has made a study of the country’s ambiguous relationship to its public memorials, told Respekt that the 30th anniversary should be an occasion, not for empty celebration, but for critical self-reflection. Since more and more Czechs are sinking dangerously into debt, he suggested erecting a monument to “The Victims of the Transformation” in front of the headquarters of a company owned by one of the richest Czech oligarchs. It was a suggestion very much in the Czech vein.

When I asked Černý if he was planning to memorialise the Velvet Revolution, he showed me, by way of an answer, a video of his next project, a reminder not of political disaster, but of the looming climate apocalypse. It’s a gigantic shipwrecked hull embedded in what will become Prague’s tallest apartment building.

If the project is realised, it could represent a major turning point in the troubled history of Prague statuary: a monument that calls attention, not to the past, but to a future we will all have to face.

Additional research by Daniela Vrbová