A Place for the Liu Xiaobo Bust

Source: China Change / www.chinachange.org / By Yaxue Cao /

In August 1988, two months after receiving his PhD in literature from the Beijing Normal University, Liu Xiaobo (刘晓波) left the Chinese capital for a series of academic visits across Europe and the United States. The first place he went to was University of Oslo in Norway. A few months later, he visited University of Hawaii, where he completed the book “China’s Contemporary Politics and Chinese Intellectuals” (《中国当代政治与知识分子》) at its Center for Chinese Studies. It seems that the purpose of his visits was to construct a framework for exploring ways to change China, and it was for this reason that he felt an urgent need to see the West up close.

In March 1989, Liu Xiaobo arrived in New York as a visiting scholar at Columbia University. According to his friends at the time, he went to art exhibitions and Broadway, and bought a leather jacket. Though the Chinese of the 1980s were still donning Mao suits, the sense was that China was on the doorsteps of a new era and a transition. All kinds of new popular vocabulary, ideas, and new “reform” trends were in the air, sparking both expectancy and uneasiness. The title of Liu Xiaobo’s dissertation, “Aesthetics and Freedom” (《审美与自由》), sounds like the name of a rhapsody.

Walking the halls of the Metropolitan Museum of Art triggered an epiphany in Liu. He suddenly felt the ridiculousness of the discussions that were taking place in China about “novel” concepts that were just everyday life common sense in the free world.

When a group of people who knew Liu Xiaobo in New York got together a few years ago for a meeting to recall their time with him (Liu had been imprisoned for six years by this point), one of his friends, a poet, said that Liu’s “enthusiasm for politics at the time greatly belied other interests of his, such as literature.”

Liu had built friendships with the small number of Chinese democracy activists in exile, and took on editorial work for their publication, “Beijing Spring” (《中国之春》).

April 15, 1989 saw the death of Hu Yaobang (胡耀邦), the Chinese Communist Party general secretary who had been ousted for his reformist stance. Hu’s death sparked memorial events in college campuses across the country. In the days that followed, throngs of students left their campuses for Tiananmen Square to pay their respects to the deceased leader. Few guessed that condolences for one man would lead to millions of people taking to the streets and voicing their political demands. Around the world in New York, the tiny group of Chinese democracy activists watched with bated breath. It’s said that at the time, at least five of them decided to return to China, and that “when it came time to depart, other four found various reasons not to leave, and only Xiaobo returned” to China.

I can almost see Liu Xiaobo’s silhouette as he gathers his luggage and hurries to the airport. Perhaps it was the call of fate. Thirty years have gone by. In hindsight, the Chinese democracy circle in Flushing was indeed too small a pond for him.

Liu arrived in Beijing on April 27, 1989 and went to Tiananmen. In the morning of June 4, he was one of the last to leave the square. From June Fourth to Charter 08 and winning the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize, and then to his death in prison two years ago, nearly half of this period of his life he spent incarcerated and forgotten, as time marched by outside the prison walls.

Even though the world had pretty much ignored him, for the Communist Party in China, it was imperative that he be completely wiped out. Death was not enough; his ashes must be thrown into the sea so as to leave nowhere for people to memorialize him.

2019 is the 30th anniversary of the June Fourth Massacre. One of the many activities being planned in anticipation is the placement of a bust for Liu Xiaobo, as he was very much a man of the June Fourth activist generation, and his aspirations belong to 1989, the year that changed the world.

In the summer of 2018, Columbia University unveiled a bust of late Czech dissident and president Václav Havel. This provided inspiration for Zhou Fengsuo (周锋锁), who chairs the non-profit organization Humanitarian China: a bust of Liu Xiaobo could also be made and erected on the Columbia campus. In 2006, Havel accepted an invitation to be a guest lecturer at Columbia and spent seven weeks there. Likewise, Liu spent several weeks here as a visiting scholar before his stay was cut short by the democracy protests in Beijing.

Liu’s widow Liu Xia (刘霞) agreed with the idea, though she expressed doubt about whether or not anything would actually come of it. The many years of her husband’s imprisonment, the monthly train trips to and from the prison in Jinzhou, Liaoning Province, her own eight years of house arrest and the abyss of depression it engendered — all this left her with a deeply jaded view of the world that lingered even after her emigration to Germany made possible by protest by the international community.

C. V. Starr East Asian Library: ‘We Must Decline the Proposal’

Last December, on Liu Xia and Zhou Fengsuo’s behalf, renowned Sinologist and Columbia political science professor Andrew Nathan (黎安友) put forth the suggestion to the Columbia president that Liu Xiaobo’s bust be donated to the university. (The following correspondences were turned over to me by Zhou Fengsuo, and Prof. Nathan has authorized the publication of their content).

The suggestion was transferred to Curator of Art Properties Roberto Ferrari, who gave Nathan a prompt reply. He explained that all artistic contributions required approval by the Committee of Art Properties, and that whether or not approval could be granted depended on there being an academic department in favor of displaying and maintaining the artwork. Ferrari noted that the Committee had recently approved the busts of Vaclav Havel and Eleanor Roosevelt, and that he was happy to work with the donor to bring this proposal to the Committee. He also said that he would make an inquiry with Jim Cheng, head of the C. V. Starr East Asian Library, as to whether they would be interested in displaying the bust.

In the following weeks, Zhou Fengsuo tried multiple ways of contacting Jim Cheng, from calls to text to email. He got no response.

On February 8, Nathan got an email from Christopher Cronin, the Associate University Librarian for Collections overseeing both Starr Library and Avery Library. He said he had discussed the matter of the Liu Xiaobo bust with Jim Cheng and Roberto Ferrari, the Art Properties curator. According to Cronin, the Starr Library would take two policies into account in deciding whether to accept a bust: first, if the person depicted had been a distinguished alumnus at Columbia; and second, if the donor was prepared to provide an endowment for the maintenance and care of the artwork.

“However,” Cronin continued, “Starr does not accept busts or statues that represent religious or political figures. As the Liu Xiaobo statue does not fit these criteria, we must decline the proposal for Starr.”

According to Cronin, the original proposal would nevertheless be submitted to the Committee of Art Properties for discussion at its next meeting, to be held in late April or early May, even though the Starr Library could not accept the bust and nor has another location on campus has been identified. He hinted that the outcome of such a submission was clear, and that “Roberto will be in touch shortly thereafter to communicate the decision of the Committee.”

I thought about Liu Xiaobo in relation to the three “criteria” Cronin mentioned. Firstly, though Liu was a Nobel Prize laureate and notable for that reason alone, he was only at Columbia for a few weeks, is he or is he not an alumnus? But if Václav Havel could be approved, why not Liu Xiaobo? Secondly, if a monetary donation was required for the acquisition, perhaps we could organize a crowdfunding event in light of the fact that Humanitarian China would not be able to foot the costs alone.

The third criterion set by the Starr East Asian Library is baffling. Excluding Liu for this reason implies that he is a political figure (that he is not a religious figure is self-evident), and that, by extension, erecting his bust would favor one political perspective over another. Now, between which political sides does the Starr East Asian Library wish to maintain its neutrality and independence?

The last time Starr Library accepted a China-related piece of art was in January 2016. A New York-based non-profit organization, the Dragon Summit Foundation (美国龙峰文化基金会), and an organization named China-America Friendship Association (CAFA, 美国中美友好协会), which is registered in New York as well, had donated a bronze bust of Tao Xingzhi (陶行知). Tao Xingzhi was a left-leaning education reformer during the Chinese republican era (1912 – 1949). From 1915 to 1917, Tao had studied education at Columbia. In addition, the Dragon Summit Foundation donated $100,000 to establish a “Columbia University Dragon Summit Fund.” The New York Consulate-General of the People’s Republic of China took part in the ceremony, and the event was reported on by People’s Daily. Another article, by China Daily, is no longer available on their website.

That August, these two organizations partnered with the Columbia University Teachers College, changing the Center on Chinese Education to the Tao Xingzhi Center for Chinese Education.

According to the CAFA website (original preserved here), in 2015, it raised $600,000 for the C.V. Starr East Asian Library of Columbia University: $500,000 for the Xu and Song Education and Culture Endowment Fund, which will “support collection, development, administration, public programming, and research at the Starr Library,” and $100,000 for a Dragon Summit Endowment Fund, which is probably the “Dragon Summit Cultural Fund” for the same library.

The Making of the Liu Xiaobo Bust

Meanwhile, the creation of the Liu Xiaobo bust started. At the end of last year, a friend of Zhou Fengsuo from the Václav Havel Library Foundation in New York put him in contact with Bill Shipsey, the founder of Art for Amnesty, Amnesty International’s global artist engagement program. In January, via Shipsey, Humanitarian China commissioned Czech sculptor Marie Šeborová to make Liu Xiaobo’s bust. The bust of Havel previously erected at Columbia University is her work.

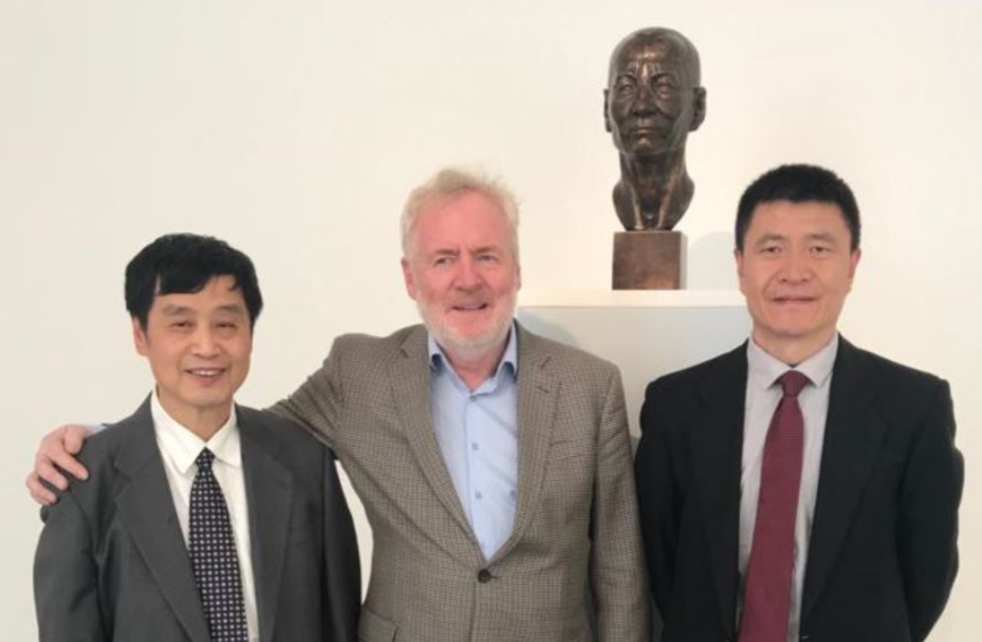

On April 15, the Liu Xiaobo bust was unveiled at the DOX Centre of Contemporary Art in Prague. Liu Xiaobo’s friends Professor Xu Youyu (徐友渔) and Zhou Fengsuo pulled the veil. Liu Xia had planned to attend but in the end didn’t make it for “personal reasons.” For the time being, the bust will be displayed at DOX.

For those looking to donate the Liu Xiaobo bust, the goal was to have it placed on the Columbia campus; the idea of it being displayed at the Starr East Asian Library was only a suggestion made by the Curator of Art Properties. The donors hope that there are other departments at Columbia University that would be willing to accept the offer, and that the Committee of Art Properties gives the matter serious consideration at its upcoming meeting.